Public-private dialogues are critical to some of the biggest policy and infrastructure developments in cross-border payments, not least the G20 Roadmap for Enhancing Cross-Border Payments. We hear from key figures at Mastercard to understand how the company is thinking about future opportunities in the space.

The future of cross-border payments is a topic that is front-of-mind for many players in the industry. While fintech challengers have helped shape the past few years of development, future change is in part being driven by multinational and supranational initiatives such as the Financial Stability Board’s (FSB) G20 Roadmap for Enhancing Cross-Border Payments.

The Roadmap, which is set to see the release of its yearly progress report within the next few weeks, lays out key performance indicators for the cross-border payments space – built on C2C, C2B, B2B and B2C data provided by FXC Intelligence – around speed, transparency and costs that both public and private entities play a part in meeting. As a result, the FSB has engaged in significant ongoing dialogue with key industry stakeholders both during the development of the targets and in the year since it published its first benchmark report in October 2023.

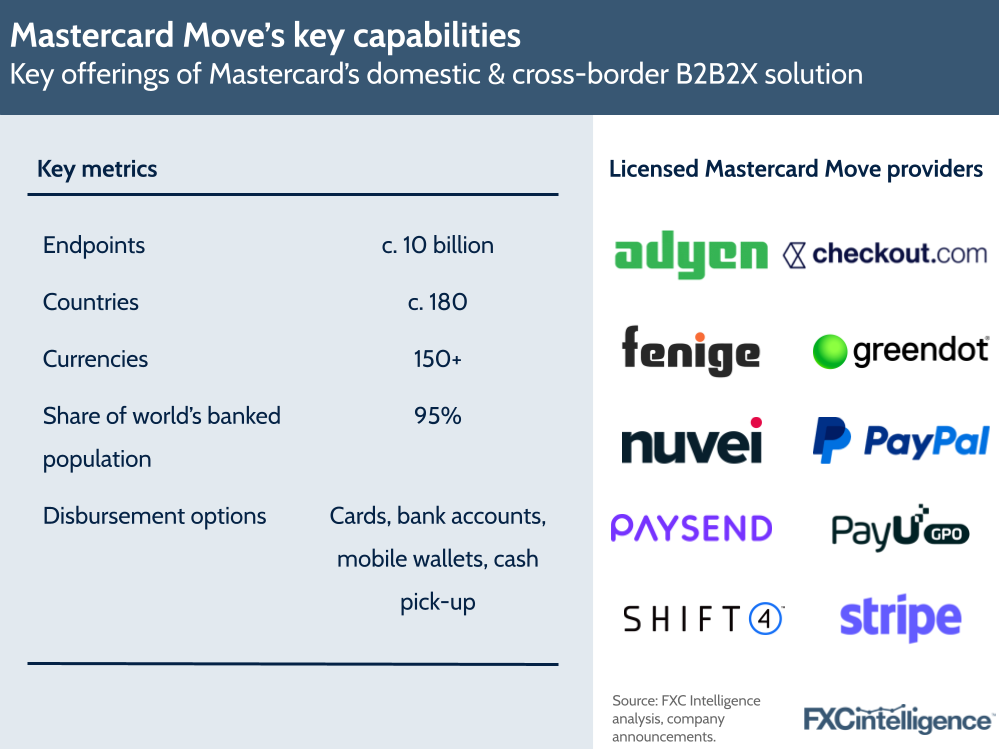

One such stakeholder is Mastercard. Although primarily known as a card issuer, the company is also a significant player in the B2B2X field, providing payments infrastructure that underpins a broad range of cross-border payments solutions globally under its Mastercard Move proposition.

“We have a well-established money transfer offering that’s partly domestic, but largely cross-border,” explains Alan Marquard, Executive Vice President, Global Head of Transfer Solutions at Mastercard.

Within Mastercard Move, remittances have traditionally dominated flows, but disbursements have become increasingly important in the last few years, particularly given the rise of use cases such as insurance payouts, marketplaces, the gig economy and the wider creator economy. The company is also “increasingly looking” at the B2B payments space.

Beyond Mastercard Move, Mastercard also runs real-time payment systems in around 12 of the world’s largest economies. And while these are inherently domestic, there is growing discussion about their interlinking and interoperability. However, while Mastercard’s current offerings are largely built on its card network, the company is also exploring digital and on-ledger style payments infrastructure.

“Fundamentally, Mastercard thinks about itself as a multi-rail entity,” says Jesse McWaters, Senior Vice President, Global Head of Regulatory Advocacy at Mastercard.

“We’re really interested in the way in which new technology might unlock new potential and new types of transactions.”

This has seen Mastercard work on the integration with CBDCs, including through collaborations with organisations such as the Regulated Liability Network, as well as its own research and development, including the creation of the blockchain-based Mastercard Multi-Token Network. The company is also one of the 40+ private sector participants in the Bank for International Settlements’ (BIS) Project Agorá, which is set to explore the use of tokenisation in wholesale cross-border payments.

As a key supplier of global payments infrastructure and contributor to such initiatives, Mastercard engages in extensive dialogue with the public sector over cross-border payments infrastructure and policy, and its leadership has considerable thoughts on how the space can and should develop.

“We spend a lot of time thinking about payment systems and payment system infrastructure,” says Marquard.

The need for different solutions for different use cases

At a high level, discussion around opportunities in the cross-border payments space has been divided between opportunities and trends in “the public sector, multinational or supranational-type space” and “competitiveness and initiatives within the private sector”, says Marquard.

For the former, this includes areas such as interoperability and public-private partnerships, aided by initiatives such as the G20 roadmap, while issues of identity, compliance and fraud are also a focus for all areas of cross-border payments. Across both the public and private sector there are ongoing debates around balancing the protection of personal data with the ability to access data to support compliance, including confirmation of payee and other related areas.

However, the solutions and approaches to that balance are quite different depending on the details of the payment in question.

“When you get into the nitty-gritty of payments, the needs and opportunities are completely broken down by sector, by flow, by use case,” Marquard explains.

“People are really surprised, for example, that in some instances speeding payments up creates more problems than it solves.”

He gives the example of instant payment systems, arguing that they have seen a significant increase in fraud due to the lack of options to undo a payment once it has been delivered, as well as having systems to deal with potential errors that are still in their infancy.

“You go from instant to the weeks and months it may take to unravel because there’s no easy framework for doing it. Whereas in the cards world, there are dispute management and quick refund capabilities,” says Marquard.

Changing mindsets around the G20 cross-border payments roadmap

This need for differentiated focuses also continues into the FSB’s G20 Roadmap for Enhancing Cross-Border Payments, which includes annual progress reports on the sector’s performance against KPIs for wholesale, retail and remittance payments.

Here, Marquard argues that “most of the concerns have been about person-to-person payments and consumer remittances”. However, while McWaters acknowledges that “there’s a lot to be desired in terms of wanting to have deeper granularity”, he also sees benefits of leadership at the top level.

“If we take a step back and think about the policy drivers behind those top-level [G20 Roadmap] KPIs, there’s both an appetite and an opportunity that become clear there,” says McWaters.

First released in 2020, the roadmap was developed in response to the increasing focus on frictions in cross-border payments from policymakers, consumers and corporates. And according to McWaters, the way the industry has thought about delivering those goals has changed considerably in the following years.

“[At first] it was tempting to imagine that we could somehow start with a blank canvas, build something new with the latest technology and, in a relatively short period of time, snap our fingers and get transformative results,” he explains, adding that those involved have since realised that “this isn’t necessarily the case”.

“The reality is that we don’t have a blank canvas: there are existing systems, there are multi-year, multi-decade investments that have been made and those aren’t going to vanish overnight.”

Beyond this, regional and national differences around regulation and data localisation, as well as broader geopolitical uncertainties, are also “foundational issues” that McWaters does not believe can be tackled purely through infrastructure or technology.

“They need to be addressed at a fundamental political level,” he explains. “For me, the most important opportunity in the KPIs is the public sector commitment to delivering change in cross-border payments.”

Here he sees Mastercard and other industry stakeholders playing a key role in engaging with this commitment.

“The role that we play while engaged in those dialogues is to educate policymakers on the specifics of the issues and, in particular, to direct them to where their efforts and political capital can be most impactful.”

Finding potential in data frameworks

While there are many ways that industry stakeholders are engaging with the G20 roadmap and wider policy-related discussions, Mastercard sees data frameworks in particular as being “really transformative” to some of the KPIS, according to McWaters.

“When we started this roadmap, we were already moving in a good direction on a lot of the elements in the building blocks,” he explains, pointing to ISO 20022 as an example of something where adoption “wasn’t happening as fast as policymakers would like, but was on track”.

He also cites The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) as a key driver of AML harmonisation, but argues that when the roadmap began, it was quite a different picture for data localisation.

“We were running in completely the opposite direction on data localisation requirements; they were contributing to cost and complexity within the space,” he explains.

“Now, after a lot of discussion and dialogue with the FSB, we find ourselves in the place where we’re talking about creating an entirely new forum that’s going to bring together the FSB and the FATF, as well as the Global Privacy Forum to address the frictions created by data localisation.”

Detailed in recommendations published by the FSB in July this year that focus on addressing data flow restrictions in cross-border payments, the proposed forum would consist of public sector stakeholders specialising in areas such as payments, anti-money laundering, sanctions and data privacy.

“We’re going to have an opportunity, I hope, to really dig into some of the fundamental underlying drivers to cost and complexity in cross-border payments,” says McWaters, “and to create an environment where both the existing systems we have and the new systems that we’re going to build can be more effective in delivering the speed, efficiency and transparency that policymakers clearly expressed that they wanted at the beginning of this process.”

This would be distinct from infrastructure, serving as the policy environment in which infrastructure was deployed and therefore have the ability to define how effective a provider’s straight-through processing rate could be.

“At the moment, complying with some of that policy – if you think about the screening – is done at the participant level and then goes through the infrastructure,” explains Marquard.

“I’d love to think about a world where identity management, the screening, was all part of an infrastructure.”

While currently conceptual, it ultimately has the potential to have a profound impact on how infrastructure in the space can be developed.

“Ultimately what we’d need to consider is what is possible when we’re imagining the deployment of new infrastructure, as well as iterative improvements to existing infrastructure,” adds McWaters.

Opportunities in interlinking payments infrastructure

Beyond policy, one of the most widely discussed topics in cross-border payments at present is in interlinking infrastructure. While there are solutions gaining traction in the private sector, with Marquard seeing interoperable solutions aimed at digital wallets being a key opportunity for example, the biggest focus of this space is on the public sector side, with the interconnection of domestic payments across borders.

Here, there are a wide variety of solutions in development. Some central banks have already signed bilateral agreements to enable interconnections along key corridors, while broader solutions such as the BIS’ Project Nexus are exploring this at a broader level that would see countries able to join a cross-border interoperable network through a single connection.

However, Marquard doesn’t believe that it is “the panacea for global access to payments”.

“There have been some new infrastructure designs put forward which are pretty innovative, and then it depends on what you call infrastructure,” he says, pointing to some initiatives to create multilateral private networks for specific use cases, which he believes “will unlock some things”.

He believes that one area with potential is trade payments, which are largely served via correspondent banking rails at present. While there has been considerable work conducted to improve their speed, traceability and overall delivery, he argues that there are still issues to tackle.

“One of the biggest pain points is around trapped liquidity and slow processing, and also just the cost of breaks and mistakes in trade payments,” he says.

“There may be an opportunity to create some kind of network, scheme or financial market infrastructure – and there are private sector schemes and networks that can be created to do the job of an infrastructure, if you will.”

Crucially, McWaters stresses that with interoperability being such a focus across the industry, “it is really important that we avoid dreaming about a world in which there’s no fragmentation, in which there isn’t the need to bridge across multiple platforms”.

“It’s easy to think about that world, but at some level that’s not viable, unless we’re all going to bank with a single bank in a single currency and you’re going to onboard a billion people into that system,” he says.

“I don’t think that the FSB would be terribly keen about a bank that was too big to fail.”

Ultimately, he instead sees the goal as being the development of use-case-specific solutions that are designed to effectively work with each other.

“Thinking about a cross-border framework that has joints – that can flex – rather than one in which all things need to be on a single, perfect state infrastructure is ultimately going to take us down a more practical and a more useful and impactful road.”

The cross-border to card opportunity

Looking to the corporate world, while there are growing opportunities in use cases related to disbursements, Marquard also sees “a big opportunity in cross-border to card”, particularly given changes in how such payments can be delivered. Historically, this space has faced challenges due to how the card and bank rails have interconnected, particularly from a compliance perspective.

“If you’re receiving a payment into an account as a bank, that will typically come in through a well-established channel. It’ll feed into your various sanction screening and AML systems that sit in one part of the institution,” explains Marquard.

“Typically, the card network connectivity is a whole different rail, so now you have a cross-border payment coming into a card rail that probably isn’t connected to all of those controls.”

This has required banks to “get comfortable” with being able to quickly screen and process such transactions – something that card networks have been building up cross-border acceptance for over many years.

“That’s grown to healthy proportions now, which is why I think we’re at the point where we’re going to see a lot more traction in cross-border to card.”

While not every use case is appropriate for cross-border to card, there are a “good set” that Marquard sees as being a good fit. These include various types of P2P payments to cards, as well as a variety of disbursement types.

“Gig payments are a really good one where you have a distributed workforce that wants immediate access. The form factor is easy; they can spend on the card quickly,” he says. “Refund-type use cases, cross-border insurance payouts are another one.”

The policy-led future of cross-border payments infrastructure

Over the past few years, there have been many improvements in the cross-border payments space, particularly around reducing costs. However, Marquard argues that this is more down to private sector competition than policy-led reform.

“The G20 KPIs have actually been important as the kind of mood music, I think, more than as a specific driver of any particular action,” he says.

“Competition is achieving some of what we always thought it would take top-down structural reform to do.”

However, with increased policymaker attention on the space, and the possibility of a compliance-focused forum on the horizon, he does see significant potential in public-private initiatives to shape the future of the industry.

“If some of these structural pain points get taken out with the help of the public sector, then I think we’ll be in a pretty positive place,” says Marquard.

“This idea of a forum that brings together all of the authorities in compliance and AML is the biggest game-changer.”

For McWaters, meanwhile, the future of the space is ultimately going to be iterative, as private sector players generate new demand that the public sector responds to. However, he argues that cross-sector cooperation will be vital to how well this is delivered.

“A key element of how far that process is able to run is going to be how effective we are in public-private forums like the G20 roadmap in figuring out ways to drive harmonisation and to remove some of the systemic barriers to faster, more efficient, more transparent and more inclusive cross-border payments,” he says.

“Those dialogues will continue to be really important and we have to take achievements like the creation of this cross-border data frameworks organisation and figure out a way to go from the start of an important conversation, that was not previously being had, to that conversation being genuinely impactful to the operating environment.”

Meanwhile, innovation and experimentation through initiatives such as the BIS’ Project Nexus and Project Agorá are also set to be key, although McWaters stresses that “the challenge comes when we look to operationalise these things”.

“Obviously the devil continues to be in the details, but it will be really important to have these two things working side-by-side: efforts to improve existing offerings and efforts to explore new transformational technologies,” he says, “all of which are underpinned by public-private collaboration and the regulatory, political and operational environment in which they exist.”